Some might find the number of coronavirus cases coming out of China weird, and I’ve heard the accusation of possible “central fabrication.” In case you have similar doubts, I’ll try to provide more information for you to decide if this argument is justified.

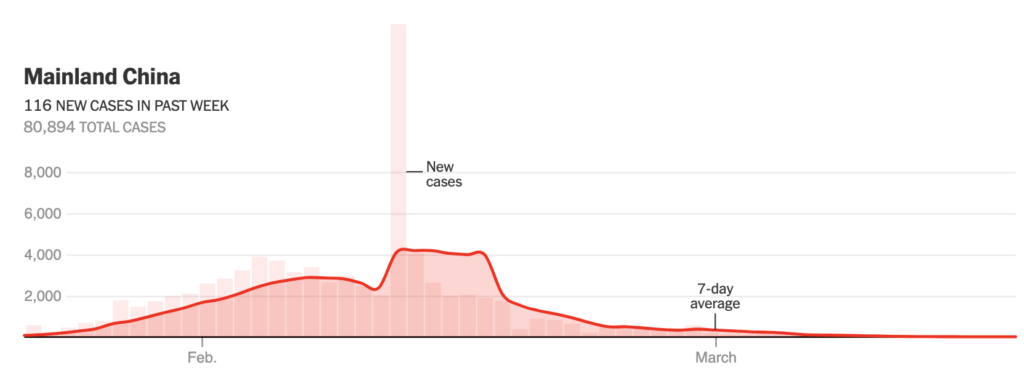

Below is a figure of reported cases in mainland China in the past two months. It doesn’t look like a bell-shaped curve as expected, but it’s too soon to jump to the conclusion of data fabrication. First, the column in the middle that stands out is an artifact due to a change in diagnostic criteria. Since February 13th, the diagnostic criterion for confirmed cases no longer requires positive PCR test results and can be based purely on clinical symptoms and CT images. The lower criterion greatly reduces the chance of false negatives, but at the same time it introduces more false positives that would be corrected later. Besides, if this curve doesn’t look natural, you might want to factor in those surging travel activities both ways around the Spring Festival, strict lockdown even in low-risk regions, and the once collapsed medical system in Wuhan and Hubei Province. The curve can’t possibly be perfect with these interventions. Lastly, as it applies to all countries right now, no data is accurate, and it’s limited by the availability of testing kits. If you have doubts in China’s data, remain skeptical in all other countries’ as well.

Another seemingly irrefutable argument is that “they could silence their doctors, what else couldn’t they do?” If you are talking about some data fabrication at a local level in the early stage, it is indeed probable, as driven by local officers’ self-interest. However, with wide access to the Internet, it’s unlikely to perform data fabrication at the national level, once the situation has caught nation-wide and even world-wide attention. Earlier in China, desperate doctors without personal protective equipment (PPEs) and Wuhan patients in critical conditions who couldn’t be treated sought help on Weibo, the Chinese counterpart of Twitter. They immediately drew the attention of millions of people whose collective memory and expression are just impossible for any government to censor. Reports about corrupted Red Cross officials in China infuriated the whole nation as their misconducts are caught on live streaming videos; the aftermath of silencing Dr. Li Wenliang also ignited unquenchable anger in public, which ultimately led to an further investigation as well as prosecution of the officials responsible for issuing the warning to Dr. Li. Such events were all well covered by the media exactly because of the incredible speed at which information spreads with modern technology. Censorship in China, while it exists, is by no means omnipotent. At this point, it is simply impossible to falsify factual information in an undetectable fashion. Right now, my friends and families in China are gradually going back to work. If the virus were still spreading domestically in China, the world economy would feel it, and the whistleblowers would be joining in a symphony.

Maybe then you’d think that I’m biased, and that I’d naturally believe what my government tells me. However, a second thought might actually find the bias to be at the other end. For most of the generation growing up in the “open-up period” in China and those who came to the US for higher education, if anything, the dominant preconception is the superiority of the West, as has been so successfully indoctrinated and popularized with the end of the Cold War. In particular, most of Chinese who ended up as international students believe that there is much to learn from countries around the world. Personally, one of the most important things I have learnt so far is to have the open-minded scientific spirit, which asks us to refuse evidence only when we can demonstrate that it’s factually compromised, and not because of our preexisting bias. Therefore it has made me quite uncomfortable to see people claiming that certain numbers are false not because they have identified any major issues with the statistics, rather because of their vague impression of the source credibility or even simply because those numbers put their traditional wisdom into question.

In addition, after we’ve been exposed to years of unsophisticated propaganda (compared to the US counterpart), it probably makes us keener in identifying more elaborate propagandas and biased narratives. In fact, it has always been amusing for me to see how propaganda, in its more sophisticated form, has become an integrated part of the common usage of language. For example, Fidel Castro of Cuba and Hun Sen of Cambodia have always been referred to with the title “dictator”, whereas the kings and princes of Saudi Arabia and the US allies in Indonesia and Chile seldom, if ever, got addressed in the media as “dictators” even as they were wielding their unchecked power to commit war crimes, implement genocide, or conduct massive oppression against their own population. I believe many can still recall that when the journalist Jamal Khashoggi was brutally murdered in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul less than two years ago, the US media somehow still thought that “dictator” is too much of a word to be used on the beloved prince and loyal ally Bin Salman Al Saudi. As a more recent example, in two tweets on March 8th separated just 20 minutes apart, the New York Times managed to demonstrate a textbook example of the distorting power of mere narratives. It emphasized that the lockdown in China came “at great cost to people’s livelihoods and personal liberties”, when the Italian lockdown was praised as a heroic decision “risking its economy in an effort to contain Europe’s worst coronavirus outbreak.” I don’t blame the NYT in particular, because in the US, not criticizing China challenges the traditional wisdom that “China sucks,” and is therefore considered bad journalism. Just today, it’s reported that Israel begins tracking and texting its citizens using its domestic spy agency. It is justified by the most upvoted comments like “extraordinary situations require extraordinary measures” and was praised for its leadership. Just think about what the headline would be if China does the same. The list goes on and on. With all the above public information covered by major media, it’s actually quite easy to note how the narratives are so different and the prejudice so ingrained. It’s funny to hear people say that other people are “brainwashed” by their government, as if that constitutes an argument. For what I know about the word, “brainwashed” people refuse to accept new information purely because of their preconception, which immediately makes it self-defeating to refuse information coming from other people because “they are brainwashed.” While sticking to one long-standing narrative and popular thought is what psychologists call groupthinking, which is probably the closest thing to the common usage of the word “brainwashing.”